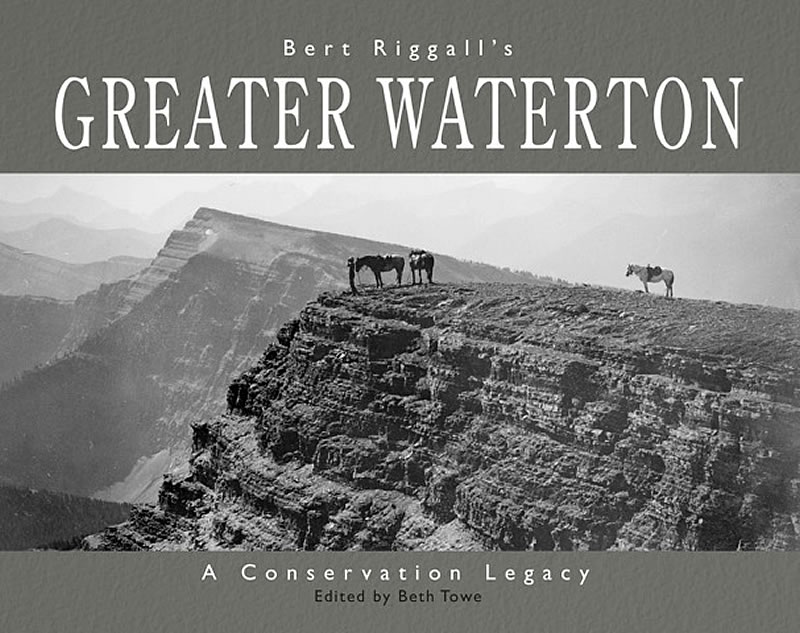

Bert Riggall's Greater Waterton,

A Conservation Legacy

Kevin Van Tighem's Full Unedited Essay - Epilogue: "God's Breath"

Calm winter days are rare in Waterton. They seldom last long. Drifts and dunes of hardened snow lie banked behind buildings in the near-deserted town where, more than a century ago, Bert Riggall began his guiding business. The lake is white and still, as if it has forgotten it is even there. Mountains gaze stonily across frozen forests at a steel-blue winter sky that stretches far off to the north.

The change begins subtly; a faint glowing halo begins to frame the peaks up near Goathaunt. Then wraiths of snow begin to dance out of the steep forests closer in. Plumes of spindrift spill from the nearer mountains – Boswell, then Vimy – and what looks like a wall of mist appears on the lake, drawing near.

Then it hits. Houses shudder. Leafless poplars writhe. A roar of sound envelopes the town and all is suddenly a chaos of wind and driven snow.

John Russell used to describe jumping into that wind from the top of the Prince of Wales hill with his boyhood friends. They leaped confidently into space, trusting the tempest to toss them back. It must have worked; he was still there, decades later, sipping coffee at our kitchen table and telling tales.

The wind was still there too, and likely always will be. The same wind that blew Bert and Dora Riggall’s first house into the creek, that fills the woods with shattered branches and blocks the roads for days at a time; the same wind that breathes the life and magic into this Waterton country. God’s breath. God’s country.

And it is that.

If God is revealed through monumental presence, one need only walk out into the bunchgrass prairie that laps up against these mountains and look out at the sacred mountains that rise here out of the Backbone of the World. Chief Mountain to the southeast. Corner Mountain in the northwest. Vimy. Crandell. Blakiston. There are stone beds atop these peaks, dreaming beds, close to the Creator.

If God is revealed through the mystery of Creation, then where better to look for evidence than in the astoundingly diverse Waterton country Bert Riggall spent half a lifetime documenting? He was only one of the first to marvel at the array of living things that combine here into some of Canada’s most biologically-diverse living communities. There are half again as many vascular plants alone, in tiny Waterton Lakes National Park, than in all four of the big national parks – Banff, Kootenay, Yoho and Jasper – to the north.

The wind helps account for some of that living diversity. Southwest of Waterton the broad Columbia plateau creates a gap in the chains of mountains that wall off the Great Plains from the Pacific Ocean. Vast seas of air surge inland across that gap, funnelled up against the one barrier that stands: the Rocky Mountains. Coincidentally – if one is content with coincidence as an explanation for the world’s many marvels – the Lewis Overthrust squeezed the Rockies to their narrowest dimension just here. And so, in a continental-scale demonstration of the Bernoulli effect, those winds come raging across the continental divide again and again, gnarling the timberline larches and whitebark pines, opening lush gaps in the lower forests, piling snowdrifts in gullies and the edges of aspen stands and scouring the bunchgrass flats clear. In doing so, it opens up dozens of unique niches for living things – and they live there.

God’s breath. God’s country. But in this secular era the idea of a god can be too laden with anthropomorphism and historical trauma for many of us to linger long around it. Even so, it doesn’t take long for the Waterton country to reawaken a sense, at least, of the sacred. The magical. Call it what you will. It’s everywhere and in everything.

Part of the magic of this place is the community of people it assembles. Of all the places in the world that Bert Riggall might have found at the end of his journey from the family home in England to find what would be his own home, he wound up here in the headwaters of a small Alberta river. Coincidence again? He was drawn to the very crown of the North American continent, and stayed. Writer, naturalist, photographer, conservationist and storyteller – he was the first and arguably the most notable of many more to follow. Waterton draws people to it who are as exceptional as the place itself.

It’s been almost two-thirds of a century since Bert Riggall died. His time was done before most of those alive today were born. In that span of time Canada has lost not just some of our finest people, but many of the landscapes and ecosystems that make us who we are. In losing their sources, we lose our stories. In losing our stories, we lose our very identity as a people. It’s a daunting thought.

But the Waterton country is not a place of loss. John Russell used to give the wind some of the credit for that – God’s breath makes it a hard place for those who want to change it. But his grandfather, Bert Riggall, deserves a lot of the credit too. In a frontier era he was one of the first to see places like this as having meaning and significance far deeper than simply as collections of natural resources to be exploited and sold. He may not have known what we now realize – that Waterton, the Flathead and the Castle together are a critical biological hotspot and living link in corridors of life that extend from Yellowstone to Yukon and from the Columbia Plateau to the Milk River canyon – but he knew that nature matters more than greed or ambition. He understood that the highest calling for any human being is to experience, study, contemplate, celebrate and protect the beauty and diversity of Creation. He found a way to make a living not by tearing nature apart, but by connecting others to it. In doing so he didn’t enrich himself; he enriched us.

Others have continued that legacy. Today, when so many Canadians live lives cut off from the nature that makes us human, the Waterton country remains for the most part as inspiring, whole and hopeful as it was when Bert Riggall first braced himself against the wind to watch the light dance across the living waters of Waterton Lake. The ranch lands along the Waterton front, carefully stewarded by generations of ranchers, are now protected by the Nature Conservancy of Canada. Farther north, the front range canyons and Castle River headwaters are now part of two new Alberta protected areas. To the west, the Flathead valley remains wild and free of settlements, hovering on the brink of new protections.

Cattle graze; grizzlies forage; sandhill cranes dance. Eagles course across the crests of sacred mountains. Bull trout scour out their nests in multi-coloured gravels below Blakiston Falls. Trilliums, glacier lilies and blue flag irises nod in golden sunshine. Bighorn rams graze the high meadows. And God’s breath sets all the land alive, as sweet in our lungs as it was in Bert Riggall’s.

Whether this is Bert Riggall’s legacy, or whether he was part of some greater legacy, there can be no question that we are all blessed by having been given a chance to share it – and to build on it.